“And when we turn to take a backward view, particularly of the years 1930 to 1950, we are always looking and looking away at the same time.”When I began this blog four years ago to document a journey across Europe looking for the locations used in two of Wim Wenders’ films, I wrote about “aspiring to feel European” and “tracing the culture that made me want to be in Europe, identifying it primarily through European cinema, through films that I saw twenty years ago” - and through reading about films, and reading about the process of making films, that I was not able to see. Clearly, such a concept as ‘European identity’ is an oversimplification; naively, perhaps, this was a definition of exclusion. In the 1980s, and into the 90s, much of the popular culture that was easily accessible when I was growing up was American: films, television, and popular music, so much so that it was simply part of the culture. Living in a relatively monoglot country makes the access and interpretation of such cultural artefacts apparently unproblematic; with shared language and literacy being a prerequisite of belonging to an ‘imagined community’, American films and music never felt as alien as perhaps they were when I was growing up: films, and to a lesser extent music (given that much popular music is sung in English no matter where it originates), from Europe always felt further away.

W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction

Inevitably, some thoughts around these ideas were on my mind in March this year, visiting Gdańsk, Poland, almost exactly four years on from my trip from London through Wuppertal and Hamburg, across the Baltic to Copenhagen and Stockholm. The events of the past four years were quite unforeseen then: this journey to Poland in March was just two weeks before the initial date set for the UK to leave the EU. On that first trip I wrote a number of loosely connected texts around the research into the locations used by Wim Wenders in Alice in the Cities and The American Friend. Subsequent trips provided material for longer, more in depth pieces. I was able to conclude my research into the former film, fittingly, with the visit to Alice’s grandmother’s house in Gelsenkirchen; I also embarked on the next stage of this project, to find the locations used in Wrong Move, the second film in Wenders’ road movies trilogy, with trips to Glückstadt and Bonn. At the same time, the experience of having done so prompted me to return to study for a research degree; in trying to define a coherent research project, inevitably I moved away from the locations of Wim Wenders’ road movies trilogy as a fitting subject. Finding the locations of the third film, Kings of the Road, would have to wait.

Two days before arriving in Gdańsk, I watched Volker Schlöndorff’s film Die Blechtrommel - The Tin Drum - forty years old this year; I’d read the novel by Günter Grass a few weeks before in anticipation of the trip. The first two books of the novel’s three part structure are set largely in pre-war Gdańsk, or, more precisely, the Free City of Danzig as it was during Grass’ childhood and adolescence, and it is these that formed the basis of Schlöndorff’s film. The novel was published in 1959, but took two decades to become realised as a film, the translation from page to screen providing numerous problems until a treatment by the producer Franz Seitz met Günter Grass’ approval and Volker Schlöndorff was attached to the project. The size and scope of the novel necessitated compression: the main narrative covers thirty years from the birth in 1924 of Oskar Matzerath, the protagonist and narrator, who decides to stop growing at the age of three as a protest at what he sees as the hypocrisy and corruption of the adult world. The novel covers his childhood and adolescence in lower-middle class Danzig before the war, the rise of fascism, the annexation of Danzig, the war years, and their aftermath, his displacement to the west, and the post-war West German economic miracle. The film ends with book two of the novel, at the end of the war. At the time, in agreeing to Schlöndorff’s film, Grass hoped that the director would then turn the last third of the novel into a second film, which remains unfilmed. In 1978, with the novel banned in Poland, Volker Schlöndorff was able to get permission from the Communist authorities to film in Gdańsk, but only a few locations were used; much of the film was shot in Germany and Yugoslavia. The film was a success both in West Germany and to a worldwide audience; the success of the novel itself, translated into many languages, prepared an audience for the adaptation. The film shared the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1979 with Apocalypse Now and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Picture the following year. In some respects, the film of The Tin Drum can be seen as both a pinnacle of the New German Cinema that emerged in the 1970s and its valedictory farewell; Volker Schlöndorff himself was resistant to identify too closely with the term: in an interview from 1981 Schlöndorff talks of the tradition of G. W. Pabst and Fritz Lang and describes Herzog and Fassbinder as “egomaniacs”, describing how the two directors’ approaches would be far from what he was trying to achieve with The Tin Drum.

The majority of the scenes filmed in Gdańsk are part of one extended sequence around the middle of the film. Outside this sequence the locations in Gdańsk used by Schlöndorff are few. The quayside opposite the mediaeval wooden crane, used for the market where Oskar’s maternal grandmother sells her goods, recurs several times during the course of the film (in the novel, she sells her wares at the market in Langfuhr, not in the centre of the city). The crane is a landmark and a symbol of the Gdańsk: in the film itself it features prominently in a painting on the wall in Oskar’s childhood home and it’s also seen in a detail of a postcard in the Polish Post Office, there doubled in its rubber-stamped franking. A second recurring motif is the panoramic view over the city, seen from a high vantage point, inserted through the film as cutaways to suggest the passage of time in different ways: once after the scene of the rally, disrupted by Oskar’s drumming from beneath the stand, a panning shot of Gdańsk separates this episode from the fateful trip to the beach at Brösen (a scene filmed on the beach itself, now Brzeźno); then, after Oskar’s mother’s funeral, a static shot of Gdańsk at twilight which leads into Kristallnacht; and the third cutaway features a static but speeded-up shot of Gdańsk as night gives way to morning and the attack on the Polish Post Office begins. In addition, there are just three shots that briefly comprise Hitler’s arrival in Danzig after its annexation: two shots shows the crowds gathered to witness this, followed by a shot from a moving car of an outstretched arm in salute; there is then a rising shot over the city which fades out.

The sequence which uses most of the Gdańsk locations begins with Oskar and his mother Agnes taking a tram into the centre of the city, meeting her cousin and lover, Jan Bronski, at the Polish Post Office. Oskar, Agnes and Bronski are seen walking together to a street corner where Bronski leaves them. Agnes takes Oskar to Sigismund Markus’ toy shop where she leaves Markus to entertain Oskar in the shop - where she leaves Oskar in the care of the shopkeeper. Agnes is then seen crossing the same street corner again. Oskar follows his mother to a narrow backstreet and looking on from outside, the scene cuts to Bronski and Agnes undressing in a bedroom. Oskar departs, upsetting a delivery boy on a bicycle with a basket of fish, the symbolism of which is apparent later in the film. Oskar is then seen sat on some stone steps, looking up at an ornate tower. There is a cut to the belfry of the tower as Oskar emerges, drums, and with his scream, shatters the windows of a building above an arched thoroughfare (the new English translation of The Tin Drum uses the compound verb ‘singshatter’ to convey the tone of Grass’ “zersingen”). At this, with a crash zoom we see Agnes looking out and upwards from an open window. The camera returns to Oskar in the belfry, travelling upwards to take in the city’s skyline.

Before travelling to Gdańsk, I had already read that the building serving as the Polish Post Office in the film was among the scenes shot in Yugoslavia, in Zagreb, Croatia. Architecturally, the building used is a good stand-in, stylistically akin to the real Polish Post Office, with a similar streetscape outside to contemporary newsreel footage: the Polish Post Office reappears later in one of the film’s set pieces, the attack on the building by the Danzig Heimwehr or homeguard on September 1st 1939, marking the beginning of the Second World War in Europe, simultaneous to the battle of Westerplatte. Although not the location used in the film, I did visit the Polish Post Office in Gdańsk. The road outside the building is now a cobbled path, the walls and railings are gone, and a large Communist-era monument commemorating the defenders of the building faces its entrance; the building itself houses a small museum.

The street corner that appears several times in this sequence was easy to identify from the presence of St. Mary’s Church in the background, which faces ul. Piwna; the corner in the foreground is its junction with ul. Tkacka. In the film, the various shots in this sequence are edited together in such a way that the viewer constructs the street scene to understand that the toy shop looks out onto this corner. In reality, the position of the toy shop is occupied by the Academy of Fine Arts - one of the few modern buildings in the centre of Gdańsk itself, but part of this also occupies the old Arsenal building; from this I assume that the toy shop was not shot in Gdańsk: I looked for a shop front that might fit, and many had similar arrangements of doors and windows in the centre of Gdańsk, but found nothing that matched up to that used in the film. However, it is just possible that the building used for Markus’ toy shop was where the editing appears to place it and this was subsequently demolished to make way for the new Academy building - but I think that unlikely. As with the location used for the Polish Post Office, the continuity in the cuts between the different locations appears fairly seamless. In the book, Sigismund Markus' shop is in the Arsenal Arcade at Kohlenmarkt which would be just behind the Academy where the film seems to place it; Agnes and Bronski use a "cheap boarding house on Tischlergasse”, some distance away by the Raduna canal, to conduct their affair, followed by meeting again after Agnes collects Oskar - as if by chance - at the Cafe Weitzke on Wollwebergasse. What was Wollwebergasse is now, appropriately, but perhaps only by a happy contingency, ul. Tkacka, used throughout this sequence in the film.

After following his mother to her meeting with Jan, Oskar retreats. He is seen sat on some steps, looking up at an ornate tower. In the commentary on the DVD, Volker Schlöndorff names this as St. Mary’s Church, but it is clearly that of the Main Town Hall (Główne Miasto, the ‘Main Town’ of Gdańsk was known as Rechtstadt in German and is occasionally translated literally as ‘Right Town’) - one can see the tower of St. Mary’s in the background when Oskar emerges at the top. The Main Town Hall is located on Ulica Długa, central Gdańsk’s grand thoroughfare which opens out onto the Long Market, Długi Targ. I examined all the steps outside the buildings along Długi Targ, trying to find the exact ones used in the film: many were similar (this is a common architectural feature of the Hanseatic burgher houses in the centre of Gdańsk, a raised terrace with elaborate stonework in front of the main entrances), and I found the steps where Oskar is silhouetted against the railing, seen from behind in a reverse shot with the object of his gaze, the tower itself, completing the composition, but these steps were not those seen in the initial shot. Looking at the double set of steps of the Main Town Hall entrance itself, I had the realisation that, in this first shot, Oskar is in fact sitting on the right hand steps of the building he is purportedly looking at.

In Gdańsk in March, the tower of the Main Town Hall wasn’t open to the public, only doing so during the Summer months. Unable to follow Oskar’s footsteps here, I photographed a bronze model of the town hall outside, with the belfry where Oskar climbs to drum and ‘singshatter’ windows stuffed with coins. I then found that it was possible to climb to the top of the tower of St. Mary’s Church, close enough to the Main Town Hall to provide similar views, but, being taller, from its cramped viewing platform, one actually looks down on the Main Town Hall’s tower, much like looking down onto its model.

The windows that Oskar ‘singshatters’ belong to Złota Brama - the Golden Gate; the glass falling from the windows is shot from the side which faces away from the Main Town Hall (one can just glimpse the balustrade and statues on top of the Golden Gate from the tower of St. Mary’s Church; from the Main Town Hall tower the view would be clearer). The camera is placed well above street level, and must almost certainly be filming from the Prison Tower (Wieża więzienna) which faces it, no doubt explaining this anomaly. In the novel this is the building that Oskar actually climbs (known in German as the Stockturm), rather than the Main Town Hall, and he breaks the windows of the Theater am Kohlenmarkt, at right angles to the Golden Gate. However, the Theater am Kohlenmarkt was destroyed in the war and an entirely new theatre built on its site behind the Academy of Fine Arts which would have precluded it being used in the film.

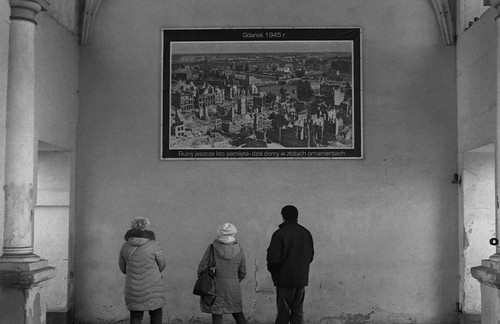

Greater than the artifice of Volker Schlöndorff, combining these disparate locations through editing into a coherent, legible whole, is the artifice of modern day Gdańsk itself. When David Bennent as Oskar Matzerath sits on the steps of the town hall to look, in an impossible gaze, at the Town Hall tower, he is not looking at the spire that Günter Grass would have known, but a reconstruction. Inside the Golden Gate, whose windows Oskar shatters, high on its interior walls are tablets containing photographs of the city from 1945. Danzig had remained largely intact until the very end of the war, when it was all but destroyed by the advancing Soviet forces: nine-tenths of the buildings in Gdańsk Main Town were reduced to rubble. The shell of the Main Town Hall did survive the war, as did the tower, but the ornate spire and belfry were lost. In some senses, the trouble taken by Schlöndorff to film The Tin Drum in Gdańsk has the tone of a reconstruction within a reconstruction: in terms of authenticity there is already the flimsiness - convincing nonetheless - of the film set about the post-war city. Many of the facades seen today are simply that - houses were completely rebuilt with exterior architectural decoration that approximates the original stylistic appearance of the city, incorporating some salvaged original elements at times, but with completely different interior plans to take into account post-war housing needs:

“…the scale, or perhaps the totality of the rebuilding, has brought not only the expected result of more or less reliable historical forms, but also irreparable loss of survived walls, vaults or details, or the authentic fabric, which by definition should be subject to architectural conservation. Similarly, to other wartime destroyed towns, Gdańsk lost its unique atmosphere or age value in the blaze of 1945. Its dispersed remnants can hardly be found today, yet we can discover authentic spoils sunk in the mass of fifty-year-old walls.”

Grzegorz Bukal and Piotr Samól, 'Authenticity of Architectural Heritage in a Rebuilt City'

As a novel, The Tin Drum is, of course, itself a reconstruction of the pre-war Free City of Danzig of Günter Grass' childhood: the first two books are forensic in their specificity of place, but written at two removes, temporal and spatial, after the destruction of the Danzig that he knew and from the distance of exile in Paris. In a chapter called ‘The Ant Trail’, Grass names the destruction:

“Now we seldom emerged from our hole. The Russians were said to be in Zigankenberg and Pietzgendorf and on the outskirts of Schidlitz. In any case they must have occupied the heights, for they were firing straight down on the city. Rechtstadt, Altstadt, Pfefferstadt, Vorstadt, Jungstadt, Neustadt, and Niederstadt, built up over the past seven hundred years, burned to the ground in three days. […] Hakergasse, Langgasse, Breitgasse, Große and Kleine Wollwebergasse, were burning, Tobiasgasse, Hundegasse, Altstädtischer Graben, Outer Graben, the ramparts burned, as did Lange Brücke. Crane Gate was made of wood and burned beautifully. On Tailor Lane the fire had itself measured for several flashy pairs of trousers. St Mary’s Church burned from the inside out, its lancet windows lit with a festive glow. Those bells that had not yet been evacuated from St Catherine's, St John’s, Saints Brigitte, Barbara, Elisabeth, Peter, and Paul, from Trinity and Corpus Christi, melted in their tower frames, dripping without song or sound. In the Great Mill they were grinding red wheat. Butchers Lane smelled of burned Sunday roast. At the Stadt-Theater Dreams of Arson, a one-act play of ambiguous import, was given its world premiere. The town fathers in Rechtstadt decided to raise the firemen’s wages retroactively after the fire. Holy Spirit Lane blazed in the name of the Holy Spirit. The Franciscan monastery blazed joyfully in the name of St Francis, who loved fire and sang hymns to it. The Lane of Our Lady glowed for Father and Son alike. Needless to say, the Hay Market, Coal Market, and Lumber Market burned to the ground. In Bakers Lane the buns never made it out of the oven. In Milk Churn Lane the milk boiled over. Only the West Prussian Fire Insurance building, for purely symbolic reasons, refused to burn down.”(In order for Grass' wordplay to work in the English text, some of the names, retained elsewhere as the German proper nouns, are here given as literal translations: the Coal Market is otherwise written as Kohlenmarkt, and so on).

In ‘Luftkrieg und Literateur’, subsequently translated into English and published as ‘On the Natural History of Destruction’, W. G. Sebald examines the lack of representation of the destruction of German cities in post-war literature:

“There was a tacit agreement, equally binding on everyone, that the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described. The darkest aspects of the final act of destruction, as experienced by the great majority of the German population, remained under a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret, a secret that perhaps could not even be privately acknowledged.”The two writers that Sebald does name as confronting this destruction, are Hermann Kasack and Hans Erich Nossack (other accounts, such as those by Heinrich Boll and Peter de Mendelssohn, written at the time, were not published until the 1970s and 80s); both Kasack and Nossack resort to elements of the mystical in an attempt to assimilate the experiences that Sebald describes. As a novel, The Tin Drum has clear affinities of the fabulous, the fairy tale about it, much of which is lost in the translation to the screen, both through the compression of the narrative and the simple constraints of what can be shown on the screen. The novel is narrated from the (then) present day, with Oskar, at the age of thirty, the inmate of an asylum, writing his life story; the film has a voice over by Oskar but it is contemporaneous with the action on screen, lacking this extra framing, and, crucially, both the fantastic and the unreliable quality to Oskar’s narration as written (in the novel Oskar introduces details out of synchrony with the narrative and contradicts aspects of earlier passages).

W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction

Like the surviving German population of Danzig, Oskar Matzerath does not suffer to live in the ruins for long, leaving the city at the end of the war, replaced by displaced Poles from the East. There is one brief sequence in the film with Oskar’s return to Gdańsk from entertaining the troops in Normandy where the remains of Bebra’s troupe drive along a street in ruins; this was a film set, built in Munich for the Ingmar Bergman film The Serpent’s Egg and later used by Fassbinder for Berlin Alexanderplatz. At the end of the film there is also one final brief shot with the skyline of the city, silhouetted behind ruins in flames. Of this brief scene Schlöndorff says, “These are in fact my first own childhood memories - burning cities at the horizon and me, six years old, standing on a hill with my brothers, looking over there, it was near Frankfurt am Mainz, seeing these burning cities, enjoying the show of it, the wonderful fireworks, not understanding that people might have been in there.”

The original cut of the film is resolved abruptly, covering several months in the novel, moving swiftly from Oskar’s return with Bebra from the Atlantic Wall to the destruction of Danzig, Alfred Matzerath’s death and burial, and then Oskar’s departure by train. In the book, there are two chapters concerning the Dusters, a teenage gang akin to the Edelweiss Pirates, of which Oskar becomes the leader after demonstrating his abilities with shattering glass, the gang are then caught and brought to trial; also important is the appearance of Herrr Fajngold at the end of the war, a survivor from Treblinka, who takes over the Matzerath shop and talks to his murdered family. In the original theatrical version of The Tin Drum, Herr Fajngold appears very briefly in two scenes at the end: the burial of Alfred Matzerath, and when Oskar leaves for the railway station: the lack of exposition here makes Herr Fajngold appear simply as a minor character. In the ‘director’s cut’ released in 2010, Herr Fajngold has two additional scenes, the first of which he introduces himself, and narrates his experience of being a concentration camp disinfector to Alfred Matzerath’s corpse in the cellar; the second scene shows him proposing to marry Maria to prevent her from being expelled (notably, among other scenes included in the director’s cut is one in which Alfred Matzerath resists signing a letter from the Ministry of Health which requests that Oskar be sent to an institution, and a subsequent scene in which he and Maria argue over this, the implication being that this institution is part of the Nazi euthanasia programme).

Apart from the Main Town Hall, the other model of a building in Gdańsk that I stumbled across was that of the Great Synagogue on ul. Bogusławski. This was destroyed just before the war and not rebuilt after Gdańsk became Polish. Its site is mostly occupied by the new Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, which, clad in black brick, looks somewhat sepulchral. This was just outside the old city walls, like the Stadt-Theater. Most of the rebuilding of Gdańsk, a combination of elaborate reconstruction and approximation, was concentrated inside the old city walls, some of which can still be seen. Outside that there are still some ruined buildings left from 1945 can be seen, but there is a lot of construction currently underway around the centre. The reconstruction (whether historically accurate or not) of cities destroyed by war was more prevalent in the East rather than the rebuilding that occurred in Western Europe. Bukal and Samól suggest that the reconstruction of Gdańsk had a political dimension, the effacing of its destruction giving legitimacy to the Polish acquisition:

“…the decision to rebuild Gdańsk in the historical spirit was the right path to take, even though the rebuilding was not a conservation aimed at the protection or resurrection of the past, but a political action undertaken to demonstrate Polish entitlement to the recovered land."My reason for being in Gdańsk was the occasion of an exhibition, ‘Made in Britain: 82 Painters of the 21st Century’, in which I had a painting on display. ‘Made in Britain’ showcased the Priseman-Seabrook Collection of British Contemporary Painting and was on show at the Green Gate, one of the National Museum’s venues in Gdańsk (which ran from 14th March to 2nd Jun 2019), and located at one end of the Royal Route, at the bottom of Długi Targ, the other side of the Main Town from the Golden Gate. Projection, my painting which forms part of the collection, was made twelve years ago, originally for an exhibition, called 'Oil and Silver', in 2007, which was concerned with the historical influence of painting on photography. It had a fairly limited exhibition history before entering the collection.

Grzegorz Bukal and Piotr Samól, 'Authenticity of Architectural Heritage in a Rebuilt City'

Projection is based on Joseph Wright’s painting The Corinthian Maid. This depicts the origin myth of the art of painting itself; Wright’s work dramatises a story from Pliny (via a contemporary poem by William Hayley) of a potter’s daughter who traces the shadow of her sleeping lover’s profile in liquid clay before he leaves for war. Joseph Wright’s picture was apt to base a painting on for the remit of the original exhibition, thanks to its place in Geoffrey Batchen’s book, Burning With Desire: Wright’s painting was commissioned by Josiah Wedgwood and painted c.1782-84; around fifteen years later, Wedgwood’s son Tom, with Humphrey Davy, experimented with silver nitrate in creating some of the first photographic images but were unable to fix them and thus make them permanent. Batchen writes that “…the ‘idea’ expressed by Wright’s painting does indeed seem to be one in which representation of any kind […] is born of a perennial desire to substitute an image for an anticipated loss”. Seen as a precursor to photography itself in its desire to fix an image, the painting combines many pertinent associations beyond that of Wedgwood’s profession (and, perhaps, Wedgwood's mechanisation of certain ceramic processes): the 18th century interest in the silhouette, mechanical drawing, in history, in ancient Greece, and the subject’s suitability to demonstrate Wright’s skill in depicting the effects of artificial light.

Projection was part of a larger group of paintings I had made around the same time, mostly showing single figures caught in an absorptive moment, some referring to the compositions of other paintings such as those by Vermeer and Edward Hopper. With Projection I wanted the use of the reference to Wright’s painting to be meaningful: some of these other paintings added little to their subjects other than the conceit of an idle modern-dress version of their sources. Key to Projection is the fact that the woman making the painting within is tracing a projected slide of the Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner in London, notable for the realism of Charles Sargeant Jagger's bronze figures and reliefs, especially that of the dead soldier at the north end of the memorial - not dead in some ritualistic quasi-mystical-religious sense of the word (“the glorious dead”) but a depiction of a very real corpse. The woman is older and is making her tracing after the war, not before, attempting, in Batchen’s words “to substitute an image for an anticipated loss” which has already happened. These images of loss and their ritualistic repetitions through state memorialisation are a mirror of the traumatic, compulsive repetitions in ‘war neuroses’ as described in the emerging field of psychoanalysis at the time, trying to prepare the self for the trauma - which cannot be assimilated - that has already happened.

The Free City of Danzig was created in the wake of that traumatic war, a fatal compromise born of the French desire for a strong state on Germany’s eastern border and the British fear of the spectre of irredentism. Without access to the sea, the newly independent state’s viability was in doubt. West Prussia, with a majority Polish population became the Polish Corridor, cutting East Prussia from the rest of Germany but connecting Poland to the Baltic; Danzig was the area’s major port, located at the mouth of the Vistula river, but with an overwhelmingly German population. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 the French were opposed to Danzig remaining part of Germany, while the British were wary of German territorial losses providing a pretext for the next war, and would violate the principle of national self-determination (the Paris Peace Treaties were full of instances where the application of this principle was not consistent; although the First World War ended with the Armistice in 1918, the break up of empires in turn resulted in numerous wars where competing states were determined to present territorial gains on the ground as faits accompli to the Allied Powers redrawing the map of Europe). The Free City of Danzig was to be a semi-autonomous city-state under the League of Nations, in a customs union with Poland, with Polish rights to the railways, port facilities (although Poland created a new port at Gdynia outside Danzig city-state in order to have a such facilities entirely under Polish jurisdiction), as well as the establishment of the separate Polish Post Office. Observers at the time were all too conscious of the problems that this was laying down for the future. Herbert Adams Gibbons, an American journalist writing in 1923 summed up:

“The resurrection of Poland could have been a glorious and blessed result of the Paris settlement had it been conceived and carried out in the interests of the Poles. But the resurrection of Poland, as provided for in the Treaty of Versailles and the supplementary treaty, was an attempt to create an artificial state for old-fashioned “balance of power” purposes. The real interests of the Poles were not considered at all. Their only hope of succeeding in rebuilding their national life lay in having boundaries that would not in the future create against them fatal antagonism on the part of their two powerful neighbors, Germany and Russia. Had Polish and not French interests been considered in writing the Treaty of Versailles, the new Poland would not have been saddled with the Danzig corridor, and Upper Silesia would have remained German territory. A combination of fear and greed, without statesmanlike vision, made a Poland that can never last. The frontiers of Poland, as drawn in the Treaty of Versailles, heralded war and not peace.”At the end of the Second World War millions of Germans were expelled from former territories in the east in order that populations might match lines drawn on the maps of Europe and Danzig became the Polish Gdańsk. Before I arrived in Gdańsk, I imagined I might discern some physical traces of the pre-war German Free City, like the manhole covers in Kaliningrad which Neil MacGregor writes about in Germany: Memories of a Nation. There is a German inscription on the Golden Gate, on the side seen in the film of The Tin Drum: only after returning from Gdansk did I read that this inscription was restored to the facade in the 1990s. Oskar Matzerath represents some of these mixed identities in The Tin Drum: he has both German and Polish fathers, and is especially close to his Kashubian grandmother who remains behind at the end of the war; in the film she sees Oskar, Maria and Maria’s son Kurt leave by train. The final shot of the film is the train passing through the potato fields where a peasant woman works, mirroring the very beginning, where we see Oskar’s grandmother as a young woman, eating potatoes baked on an open fire in the fields.

Herbert Adams Gibbons, Europe Since 1918

Much of the first two books of The Tin Drum revolve around Oskar’s life in the suburb of Langfuhr rather than in the centre of the city, and this is represented in the film. Langfuhr is now Wrzeszcz (renamed after the war, before Oskar leaves for the West, this is described in the novel as “a name that almost defied pronunciation”). Grounded in the Danzig of Gunter Grass’ childhood, as with the action that takes place in the centre of the city, Grass is also autobiographically precise about the topography of Langfuhr, the street names, the buildings, parks, trams, shops. Oskar’s father, Alfred, runs a shop selling groceries, which features prominently in the film, as did the Grass family, living behind the shop on the same street as mentioned in the novel. Grass returned “…in the early summer of 2005”:

“…ten translators, including Breon Mitchell, joined me in Gdańsk with one set goal in mind: to create new versions of my first novel in their own languages. To prepare myself for their questions, I reread The Tin Drum for the first time since I'd written it, hesitantly at first, then with some pleasure, surprised at what the young author of fifty years ago had managed to put down on paper.In the research I was able to do before going to Gdańsk, I was unable to match what was onscreen with what appeared to be the contemporary reality of Wrzeszcz; once there I felt compelled to discover whether or not this was the case. As the novel is so explicit about its locations, the only difficulty in finding them was fitting the German names to their contemporary Polish equivalents. I was aided in this by maps of Danzig from 1920 and 1940; the 1920 map covered the city centre and its various suburbs and was detailed enough to show all the street names.

For eight days the translators from various lands questioned the author; for eight days the author talked with them, responded to their queries. During breaks I would take them to this or that spot mentioned in the rapidly shifting narrative of the novel.”

Günter Grass, introduction to 2009 Breon Mitchell translation of The Tin Drum

Early on the Saturday morning, I took a no.3 tram to the stop at Kolonia Uroda and walked around a large building site where new apartment blocks were being erected to find the cemetery in Zaspa at the corner of Boleslawa Chobrego and Leszczyńikich. In the novel, after the defence of the Polish Post Office, and Oskar’s subsequent hospitalisation, Oskar is taken to the cemetery by Crazy Leo, who appears earlier in the novel at Oskar’s mother’s funeral (“Crazy Leo’s occupation was to turn up after every funeral - and no one took leave without his knowledge - wearing white gloves and a shiny black suit several sizes too big for him, to await the mourners”). Crazy Leo discloses to Oskar a single shell casing from a rifle cartridge with which he leads Oskar along Brösener Weg (now Boleslawa Chobrego) to the “run-down abandoned cemetery at Saspe” and then out through “a small, gateless portal” to a patch of sandy ground outside the northern wall of the cemetery (this may have symbolic associations: outside the northern wall, a burial place in the shade which never sees the sun) There is a portion of freshly whitewashed wall. This and the single shell casing lead Oskar to understand that Jan Bronski is buried here, in a mass unmarked grave, along with the other defenders of the Polish Post Office. Before leaving Oskar, Crazy Leo drops something into the sandy ground with a “calculating gesture” that on inspection is a playing card - the seven of spades. This detail is absent in the film, but Crazy Leo is seen with a card tucked into his waistcoat; the playing card is explicitly described as a skat card in the novel, skat being a game requiring three players, which Agnes, Jan and Alfred Matzerath play, and Jan plays with Oskar and Kobyella during the attack on the Polish Post Office after Kobyella is wounded. At the end of the war, Alfred Matzerath, Oskar's German father, joins his Polish one in Saspe, killed by the Russians while choking on a Nazi party badge he was trying to swallow, buried in a coffin constructed from margarine boxes; Crazy Leo appears once more.

The description of the topography of this location in the novel maps onto the cemetery at Zaspa: there is still an entrance in the northern wall. However, the walls of the cemetery are evidently post-war, made up of interlocking concrete crosses, and the grave markers inside are similar concrete designs, marking victims of the Stutthof concentration camp. There is a more recent brick memorial to the defenders of the Polish Post Office, whose remains were only discovered in 1991 (one wonders whether there was local hearsay that led Günter Grass to include this detail in his novel three decades earlier). At the time that the novel is set, the cemetery at Saspe was surrounded by open land, with Brösener Weg connecting the suburb of Langfuhr and the separate seaside town of Brösen; part of this open land was a large airfield just north of Langfuhr at the time when such facilities were literally fields. In the film, the location used for the brief cemetery scenes is clearly not Zaspa itself; it is however evocative of the description in the book - “run-down and abandoned” - and the sea can be seen in the distance, which might just have been possible at the time (in the novel, Crazy Leo runs off in the direction of the coast, leaving Oskar alone to pick up the skat card). The area around the cemetery is now built up, with Communist-era blocks surrounding the northern edge of the cemetery. There is still some open ground between this housing and the cemetery wall, with a path worn into the grass alongside it. There are some benches, a playground, a place to hang laundry. In front of the gate in the northern wall there is now a small car park with some recycling bins.

From Zaspa, I walked to Wrzeszcz. I hadn’t brought a map with me which covered the contemporary city this far, but rather than taking a tram back towards the city centre, then another out to Wrzeszcz as originally intended, Zaspa seemed close enough to walk to Wrzeszcz. I might not have taken the most direct route, but the route I did take led me past rows of workers’ cottages which reminded me of the Gelsenkirchen of Erdbrüggenstraße; bisecting Aleja Legionów at the tram stop there, I realised I was one stop from Plac Komorowskiego (formerly Max-Halbe-Platz; in the novel this is where Oskar meets Crazy Leo at the corner with Brösener Weg before Leo takes him to Saspe), the stop I would have alighted had I come to Wrzeszcz on the no.2 tram from the city centre.

Away from the broad dual carriageway and tram routes of Aleja Legionów, Wrzeszcz here has a very distinct character: close streets of three- or four-storey stucco-fronted pre-war terraced housing opening directly onto the street with courtyards behind. The location that stands in for Langfuhr in Schlöndorff’s film has similarly distinct characteristics but is not contemporary Wrzeszcz. The house on Labesweg, now ul. Joachima Lelewela, which was the Grass family home and shop, and is the Matzeraths’ in the novel, is marked with a plaque. Behind the houses, especially along the Strzyża, one can glimpse the courtyards, recreated in the film, where Oskar is bullied at the hands of other children, forced to drink a soup concocted of frogs, brick dust, urine, spit, vomit; the architecture of these courtyards brought back memories of having seen Sharon Lockhart’s film Pódworka in Liverpool many years ago (Pódworka beautifully observes children playing unsupervised in yards in Lodz, Poland, rather than Gdańsk).

Although it was obvious that ul. Joachima Lelewela hadn’t been used in the film, many of the adjacent streets were so close architecturally that I did wonder whether any part of the film might have been shot here, but in wandering these streets, I couldn’t identify any specific shots from the film; I did however find more of the locations from the novel: the school which Günter Grass attended, and which Oskar spends just one day, Kleinhammer Park, now Park Kuźniczki, and the brewery which abuts it - in the film of The Tin Drum, there is a brewery visible in the background of the scenes set outside the Matzeraths’ shop, appropriately part of the streetscape. The brewery site in Wrzeszcz is now part of a large redevelopment, with little of the original buildings remaining.

At the western end of ul. Joachima Lelewela is Plac Wybickiego, a small park contains a bench with statues of Oskar, installed in 2002, and of Günter Grass, united with Oskar after the death of the author in 2015. In contrast to my various trips in pursuit of the locations used by Wim Wenders, in, among others, Glückstadt, in Wuppertal, and in Gelsenkirchen (which especially felt like a very singular pilgrimage, finding Alice’s grandmother’s house), there is something of a Günter Grass tourist industry in Gdańsk, with notable places of interest from the author’s life and from The Tin Drum listed on travel websites, plotting routes one can walk around the streets of Wrzeszcz with detailed signposts at appropriate locations. One result of this interest is that the drum sticks that the statue of Oskar Matzerath holds in Plac Wybickiego are regularly stolen: when I visited, his left hand was empty.

Bibliography

Herbert Adams Gibbons, Europe Since 1918, Century, New York 1923

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, Revised edition, Verso, London 2006

Peter Arnds, 'On the Awful German Fairy Tale: Breaking Taboos in Representations of Nazi Euthanasia and the Holocaust in Günter Grass's Die Blechtrommel, Edgar Hilsenrath's Der Nazi & der Friseur, and Anselm Kiefer's Visual Art', German Quarterly, Fall 2002

Geoffrey Batchen, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography, MIT Press 1999

Grzegorz Bukal and Piotr Samól, 'Authenticity of Architectural Heritage in a Rebuilt City. Comments to Vaclav Havel’s Impression after His Visit in Gdansk in 2005', 2017 Retrieved from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/245/4/042010

Günter Grass, The Tin Drum, translated by Breon Mitchell, Vintage, London 2010. First published as Die Blechtrommel, Hermann Luchterhand Verlag 1959

Richard Grenier, 'Screen memories from Germany', Commentary, June 1980

Carol Hall, 'A Different Drummer: The Tin Drum Film and Novel', Literature/Film Quarterly; 1990

John Hughes, 'The Tin Drum: Volker Schlöndorff's "Dream of Childhood”', Film Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Spring, 1981)

Sharon Lockhart, Pódworka, 2009 http://www.lockhartstudio.com/index.php?/films/podworka/

Neil MacGregor, Germany: Memories of a Nation, Penguin, London 2014

Robert Priseman, Made in Britain, Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku, Gdańsk 2019

W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction, Penguin, London 2004. First published as Luftkrieg und Literateur, Carl Hanser Verlag 1999

Volker Shlöndorff, Die Blechtommel, West Germany 1979 (see https://www.movie-censorship.com/report.php?ID=448837 for a detailed comparison between the original DVD version and the 2010 Director’s Cut; see also director's cut press notes: http://www.janusfilms.com.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/tindrum/tindrumpressnotes.pdf )

Zaspa Cemetery – KZ Stutthof – Victims of Hitler’s Terror – Gdansk, Poland: https://www.landmarkscout.com/zaspa-cemetery-kz-stutthof-victims-of-hitlers-terror-gdansk-poland/

No comments:

Post a Comment